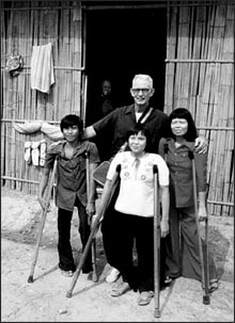

Imagine yourself in a dangerous country where you don’t speak the language and the enemy is after you. The enemy hides behind the innocent while stalking you, and you don’t know when he will strike. I know such a man who faced this kind of danger, and I want to share a little bit about him because, although we never met, he influenced my life and my novel Pretty City Murder. His name is Father Joe Devlin SJ. Father Joe was a Jesuit missionary in Vietnam from 1970 to 1975. He fled Vietnam on one of the last helicopters to lift off from the American Embassy in Saigon at the end of April 1975. Father Joe later said he could be seen on American television as the events unfolded. I am connected to Father Joe through his brother, also a priest. Father Ray was my brother’s high school religion teacher and gave us instruction in the faith at home. San Jose State University Professor Larry Engelmann interviewed Father Joe for the April 1999 issue of Vietnam magazine. I found the interview when I googled Father Joe’s name, and I was pleasantly surprised at the exchange between the professor of a secular university and a priest who otherwise could have been overlooked by history. In the interview, Father Joe does not recount the threats to his life during his years in Vietnam but focuses, instead, on the efforts to get out of Vietnam and extricate his people, the refugees he had helped at Camp Pendleton. Later, he refers to the plight of another group of Vietnamese refugees who fled to Thailand. His account of their ordeal is both horrifying and uplifting. In the interview, Father Joe said, “Someone from the CIA came to the village and tried to get me out and to Saigon. I went along because they ordered me. And when I got to Saigon I went to see George Jacobson at the U.S. Embassy and said, ‘Mr. Jacobson, please, I left my village too soon and I want to go back to it. Do you think you can help me? I don't want to run away like this.’ He replied, ‘I understand. We have a small plane going to Nha Trang this afternoon, and if you want to get on it, you can, and it will drop you off at Phan Thiết.’ So, I got on it and went back to my people, and they gave me a big ovation when they saw I'd come back.” This speaks to Father Joe’s selfless concern for his people, which is the highest form of Christ-likeness few of us will ever be forced to exercise. As I delved further into the interview, I discovered something else -- the source of my peculiar kind of Catholicism. Father Joe said, “I never put what I did in a religious context. There is a famous expression: Primum est esse, quam esse tale. It means that before you become something, you have to first exist. With the refugees I thought it was more important . . . to try to keep the refugees in existence, give them being, before I tried to make Catholics out of them . . . Because, as that expression [Primum est] tells you, you must first keep a man in existence before you try to make him something different. A man or woman must be able to live first before they can become anything. So, my effort has not been, primarily, a religious effort. Because I don’t like to change a person’s religion. I want him to do his own thinking and then do what he thinks is the proper thing. But there is a very important step in his life first, and that is to keep him in existence, to hold him up, to be his brother . . .” I found myself agreeing with the Latin phrase, Primum est esse, quam esse tale – before you can become anything, first you must exist. My personal contact with the Vietnamese diaspora in San Francisco and San Jose in the 1980s can attest to that. I did not try to convert anyone. I attended several Buddhist services, but I never considered another faith, and I was never a seeker. I had already found truth. Nevertheless, in my own ragged way, I tried to help the Vietnamese exist in America. In the process I had to apply what I knew to situations which were sometimes difficult, awkward, or unfamiliar. In a previous blog post called My Experience with the Vietnamese Community, I described how I had to push through situations as best as I could; I may have erred and rationalized, but I was always learning . . . and learning from others who were like me, yet different. As I continued to read the interview, I saw something more startling. Father Joe said, “I don’t feel guided by the holy spirit or anything in my work. Not really. I don’t look at my work with the Vietnamese from a religious point of view. I pray but not too much. And my prayers are not always answered. I never expected divine intervention in Vietnam. I just felt that God . . . says, ‘You got to do your own work, fella. So, do it.’ And so, I did it.” Like Father Joe, I don’t pray that much, and I don’t ask God for help. Many Catholics would criticize me for saying that, but, like Father Joe, I know God expects me to do the work. He just watches. I don’t expect divine intervention, although there are times when I ask for it. Has divine intervention ever happened in my life? I don’t think so. God has come to me through my parents, three conversion experiences before I reached 18, and other people, some in small ways and others, mostly priests and largely in the confessional, in a big way. Father Joe may have lived a heroic life in Vietnam, and it’s possible he could be canonized someday, but we should step away from a fascination with saints long enough to hear the real feelings and thoughts of a man who only did what he thought was necessary. Father Joe’s Catholicism and its impact on his people was real. The way he applied his faith was multiplied like the loaves and fishes by the people he cared about, as reflected in the following quote: “I think the people I helped remember me sometimes. I think I live in their hearts . . . I can remember their faces but not their names. I can’t even speak their language. But I am sure they remember me . . . If they remember me, they will someday be inspired and perhaps do good also, and if they do, when they do, then what I did was worth it . . ..” What I learned from Jesuits like Father Joe is real and practical, namely, duty and purpose. Most men are task oriented, and my brother and I and the Jesuits are no exception. The Jesuits gave us an understanding of what a man is and what he should be about, and for that, my brother and I will be grateful forever. Here are some links to the interview and other treasures: http://www.historynet.com/joe-devlin-the-boat-peoples-priest.htm http://boatpeople75.tripod.com/The_Boat_People_Priest.html http://www.vietnamexodus.info/vne/forgetmenot/father_joe/joe1.htm For more about Father Joe, there is a short biography on Amazon which can be found here Vietnam is about 10% Catholic, and the faith is flourishing. Learn more here For those interested in a little more about history, see a fascinating Fordham University speech given by Madame Nhu, an important and influential Catholic in Vietnam during the 1960s. Then, check out my novel, Pretty City Murder, and try to figure out how the novel multiplies Catholic realism and the peculiar kind of faith best exemplified by Father Joe.

2 Comments

Shelley Smith

10/23/2018 05:40:27 am

Powerful meaning how he was willing to go back. Most people are afraid to face death.

Reply

10/24/2018 06:11:12 pm

Thank you, Shelley, for the comment about Father Joe. I agree with what you said. Bob

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed